A Scarborough writer traces echoes of home in a town that’s still trying.

By: Marie Pascual

I didn’t expect Brantford to remind me of Scarborough. Not in flavor or energy, but in the stubborn ways people still try. It hit me somewhere between the church with automatic doors, the protest signs zip-tied to someone’s porch railing, and the laundromat sitting beside single-family homes.

As I walked through Sunrise Records in Lynden Park Mall, déjà vu crept up on me. I was scanning the “Hip-Hop” section when a collector’s vinyl of My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy, priced at $119, caught my eye. I turned it over in my hands and started tuning in to the music playing overhead:

“Bones, sinking like stones / All that we fought for…”

Even as I write the lyrics now, a soft, warm feeling hangs over me. It was Coldplay’s “Don’t Panic,” from 2000. I grew up on early-2000s alt rock. Back before streaming, it was just me, 102.1 The Edge, and the backseat of my mom’s Hyundai, watching raindrops race across the window. Waiting for friends outside HMV at Fairview. Feeling like I was on the edge of something I didn’t know how to name yet.

This town reminded me of that feeling.

“We live in a beautiful world.. yeah we do”

“You ready to go?” Andy asked.

I snapped out. “Yep. Just about.”

That’s when I remembered: we were about 150 km west of Toronto, in Brantford. My partner and I had joined our friend Andy on one of his work trips. Brantford, I’d read, was the birthplace of Alexander Graham Bell. Industrial roots. Inventorial pride. I expected something more.

Andy had warned us. Low-income neighborhoods. Limited infrastructure. Not much to do. Still, that Scarborough part of me—the part that finds meaning in underloved places—was curious. So we drove.

Brantford sits on the Haldimand Tract—land promised to the Six Nations of the Grand River in 1784. That history still lingers, if you’re paying attention. The city’s grown slowly in recent years, hovering around 105,000 people now, but it feels like a place that’s been treading water. One of its biggest employers, the 100-year-old Maple Leaf plant, is expected to shut down by 2025.

Driving in felt dreamlike. Hills scarred by dangling wires. Churches on every corner, most built in the 1800s, fading into the brickwork of early settlement.

“Look, ye olde telephone poles,” Nelson joked, when one almost scraped the sky above a house.

We passed a small bungalow with two signs staked into the front lawn:

WE NEED A HOSPITAL — CALL OUR PREMIER

SAVE OUR GREEN SPACE

At first I thought it was just someone’s personal crusade. But later I searched up Brantford General. Hundreds of complaints—eight-hour ER waits, staffing shortages, people walking out untreated. If I lived here, I’d probably put up a sign too.

As we drove deeper into town, I started noticing people walking with all their belongings. Duffel bags, torn strollers, carts. A woman dragging a small suitcase behind her like it was all she had. The numbers say fewer than 250 people in Brantford are unhoused. But it felt like more. More than half of those recorded are Indigenous—a reminder of who’s always been here, and who’s been let down the longest.

We kept seeing contradictions. A saloon-styled Wild Wing with iron bathroom locks and bolted-down booths. Vape shops filling what looked like once-abandoned lots. Old churches with automatic doors. Brantford feels like a town that only fixes what it has to, or what still gets donations.

We parked near the Bell Memorial. Saying “local neighborhood” feels redundant. Brantford is stitched together with small plazas, houses, and trailheads. One plaza had a coin laundromat next to detached homes. It made me pause. If people have houses, why laundromats?

Andy and Nelson pointed out the Wilfrid Laurier and Conestoga campuses. A lot of these homes might be student rentals. Suddenly the random scooter we passed made more sense. PEVs work here. There are trails everywhere.

We took ours out too—me on my Onewheel, Nelson on his EUC, Andy on his scooter. Somewhere along the Grand River Trail, a guy on a BMX zipped past and flashed us an “okay” sign, like we were part of some unspoken club. It made sense. The city’s stitched together not by subway lines, but by bike paths and shortcuts.

When we finally reached the Bell Memorial, I looked around. Mostly older white folks. Some young Black adults. A few Middle Eastern families. Practically no Asians. Scarborough, by comparison, is over half of the visible minority. Brantford felt more like a town you’d pass through on an American road trip than a pocket of southern Ontario. Still, you’ll see “No Guns” signs taped to storefront windows. This is still Canada.

The memorial itself was awkward—wedged between three intersections, more of a hangout spot than a destination. But the area around it surprised me.

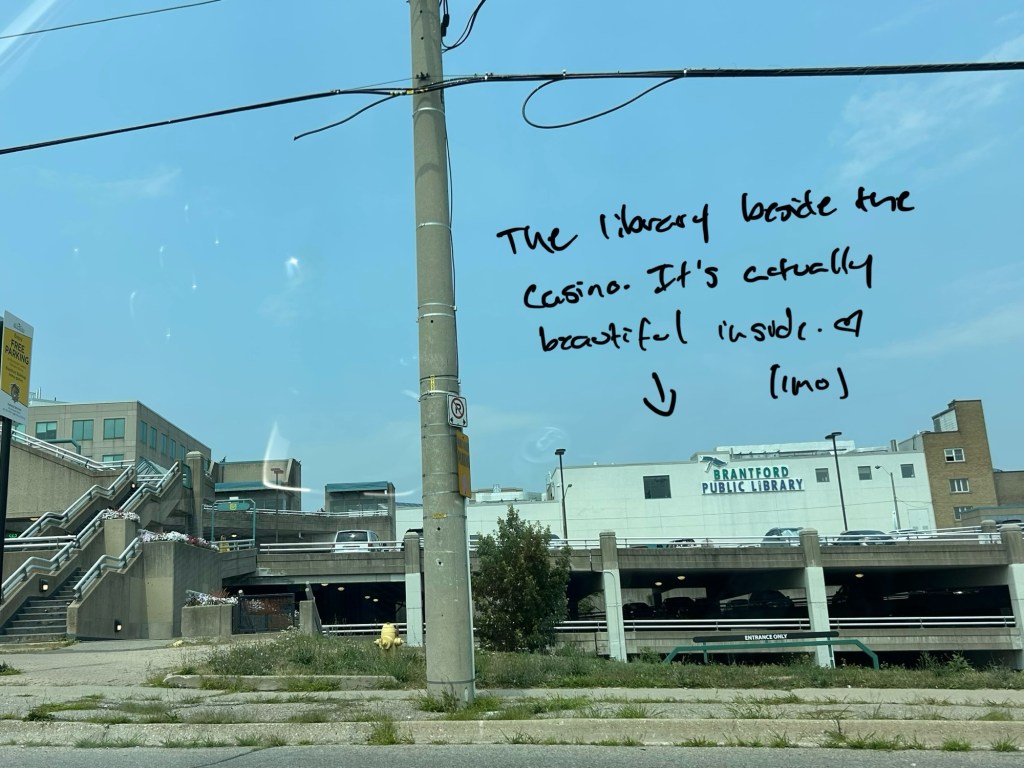

Within walking distance: the casino, the main public library, and Earl Haig Family Fun Park. A strange civic triangle that feels like a downtown designed in Sims. The park itself reminded me of Kidstown, the splash pad I grew up with in Scarborough. There’s something kind of sweet about a city still fighting to hold onto summer joy.

We saw a few Jamaican and Indian spots too—but they were tucked away, easy to miss. Hidden in strip malls. Disguised under names that don’t scream “jerk chicken” or “butter chicken combo.” Like the culture’s here. Just quieter. Keeping its head down.

That evening, we followed the trail until it opened up by the water. Brantford has these benches that swing, just lightly, with their backs to the traffic and their faces to the Grand River. We sat for a while, letting it rock beneath us. The sun was setting. People passed in pairs. It felt like a town trying to make space for rest.

After our wheel around the trail, we ended up at a place called Crazy Canuck. I didn’t think much of it—just somewhere to use Andy’s work meal credit. It was bright and mostly empty. CP24 played in the background. The older woman who greeted us barely smiled. But when the Canuck Feast arrived, something shifted. She saw our faces light up. The ribs were perfect—saucy, charred, tender. “This is better than Scarborough Ribfest,” I said. The woman finally cracked a smile.

Turns out her name was Heather. She’d been working Ribfest for decades before opening this place—right before the pandemic hit. It took nearly two years to open. I told her it was a blessing they were still around. As I cleaned the bone of a second rib, I realized why the name “Crazy Canuck” had sounded familiar.

I’d been eating her ribs my whole life. Every summer at Ribfest, waiting in line with my mom. These ribs were part of my childhood.

And now, I was here, eating them fresh. In this weird little town. Realizing it wasn’t so far from home after all. As we sat there, finishing dinner, Coldplay drifted back into my head.

“We live in a beautiful world.. yeah we do..”.

We might have better transit. More food. Bigger variety. But they have the river. They have walkability. They have benches that face the sunset. And they have people choosing to stay, choosing to live here, even when it’s hard.

And maybe that’s why Coldplay hit me so hard. Back in Scarborough, I’d sit in the back of my mom’s Hyundai while that song played, watching her grip the wheel tight. Some weeks, we barely had enough. But music softened the air. Made things feel okay, just for a moment.

Brantford reminds me of that version of Scarborough. That early-2000s in-between time, when things felt smaller, patched together, but full of people still trying.

If you grow up in places that aren’t built for you to succeed, you learn to notice who keeps showing up anyway. You learn to find beauty in what remains.

And that’s what Brantford is doing. Just showing up. Still here. Still trying.

Leave a comment